Jan 18, 2026

Can India’s 75 Year Defence Journey Make it a Dark Horse?

Deep Tech

Profile

Last month, the United States picked up Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro from his home to increase hostilities, as India reported a surge to 26,000 Cr of defence exports.

Independence Without Armour

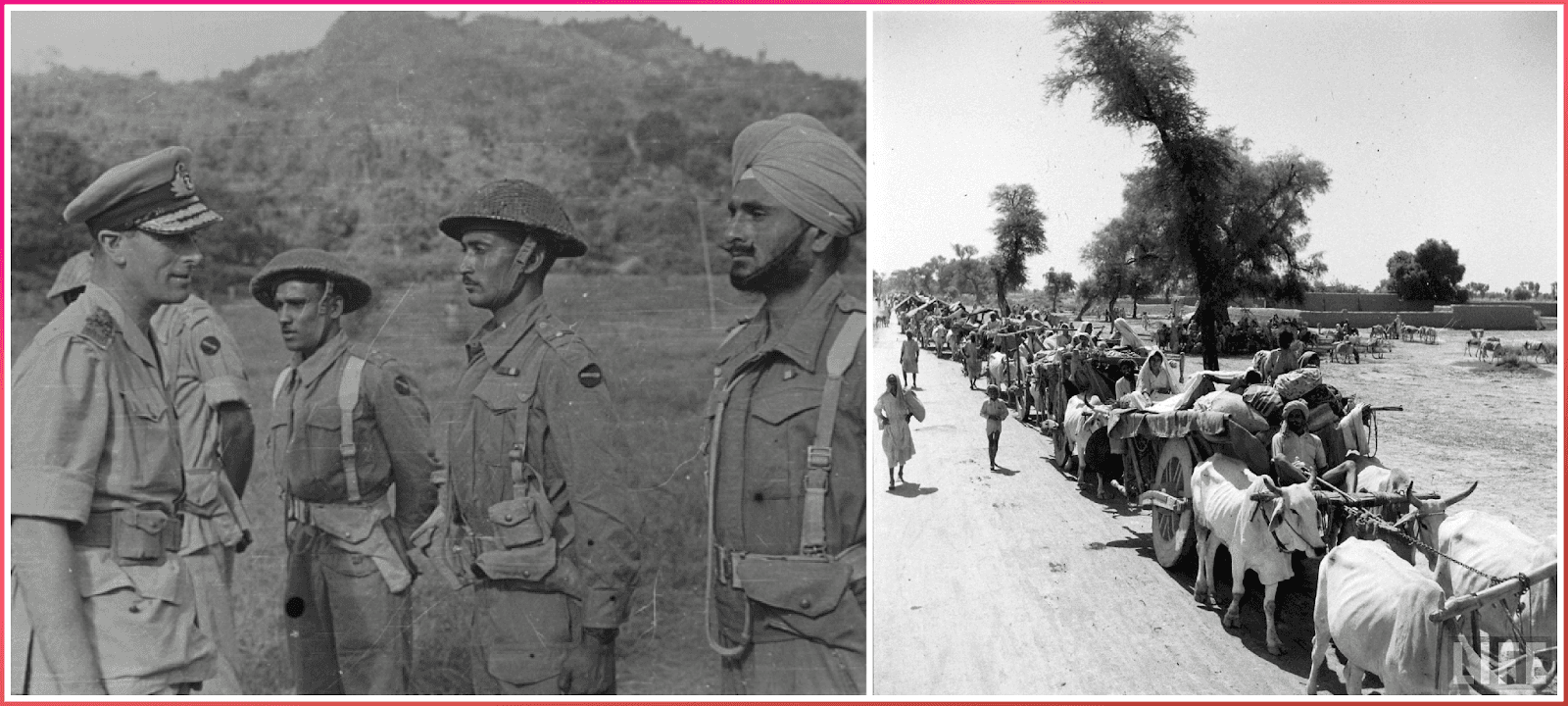

In August 1947, India woke up as a free nation amid chaos.

The British Empire left behind borders drawn in haste, two hostile neighbours, and a subcontinent still burning from Partition. Trains packed with refugees crossed newly cut frontiers. Cities bled. And a young nation of nearly 340 million people stood up with a flag, an army, and very little control over how wars were actually sustained.

India inherited close to three million soldiers from the British Indian Army, one of the largest standing forces in the world. As the British left in haste, they did not inherit sovereignty over the systems that keep an army alive in conflict. None of the domestic production, secure logistics, resilient supply chains, and the ability to repair, replace, and resupply at speed was available.

The ordnance factories left behind by the British were designed to service a colonial force, not to equip a sovereign military. They could maintain rifles and produce basic ammunition, but they were not built for scale, iteration, or technological evolution. By the early 1950s, more than 70% of India’s rifles, artillery, vehicles, radios, and spares were imported. Defence spending hovered around 2% of GDP, yet a majority of that expenditure flowed straight back out of the country through foreign invoices.

At the same time, the global order was hardening. The Cold War was taking shape. The United States was rapidly militarising Pakistan as a regional counterweight to Soviet influence. China, newly unified under the Communist Party, was consolidating control over Tibet and building infrastructure deep into its western frontiers. The Soviet Union was pouring resources into aircraft, missiles, and nuclear forces.

India chose a different path.

Under Nehru, the country placed itself at the centre of the Non-Aligned Movement, refusing to formally side with either superpower. It was a morally coherent position, but a strategically lonely one. Non-alignment meant the lack of a defence umbrella, guaranteed arms pipelines, and wartime backstop.

India did have factories, workshops, and state-owned production units. It did not yet have indigenous defence stacks designed for iteration, integration, and technological evolution. There was no aerospace ecosystem capable of rapid upgrade cycles, no military electronics base building sensors or secure communications at scale, and no indigenous missile or radar programmes that could evolve under pressure.

Even basic requirements, such as winter clothing for high-altitude warfare, depended on external suppliers. India could parade soldiers. It could not sustain a modern, technology-driven war on its own terms.

Change was afoot.

From Humiliation to Hardware

1962’s defeat ended the idea that independence could be defended solely by intent, diplomacy, or bravery.

A nation that had just discovered how alone it was, began to do something it had never done at scale before. It had to build for war. Defence spending jumped sharply after the Himalayan defeat, climbing beyond 3% of GDP by the late 1960s. The real shift was not the size of the budget, it was where the money went. For the first time, India began to redirect defence capital away from foreign suppliers and into domestic production capacity.

The Ordnance Factory Board expanded aggressively, growing to more than 30 factories spread across the country. These were not glamorous facilities. But they produced the things that decide long wars. Rifles, machine guns, artillery shells, propellants, fuses, and explosives.

India gained the ability to manufacture millions of rounds of ammunition every year. That meant if a conflict dragged on, India would not be waiting for ships to arrive from Europe or the Soviet Union to keep fighting.

In parallel, Hindustan Aeronautics Limited was given a mission that went far beyond assembly.

Founded in 1940 in Bangalore, HAL became the backbone of Indian air power. Soviet aircraft, such as the MiG-21, were assembled, overhauled, and eventually partially manufactured in India. By the late 1960s, HAL was maintaining hundreds of fighters, ensuring that even if foreign supply lines slowed, the Indian Air Force would not be grounded.

Shipbuilding followed the same logic. Mazagon Dock and other yards began serial construction of warships. India might still buy designs or key systems from abroad, but hulls, maintenance, and fleet readiness would now be domestic.

India also made a geopolitical choice that shaped its defence industry for decades. It locked in a deep partnership with the Soviet Union. In exchange for political alignment, India received tanks, aircraft, submarines, and missile technology on an unprecedented scale. The platforms were Soviet. The sustainment was Indian.

This hybrid model was powerful. It meant that in peacetime, India could import advanced weapons and, in wartime, keep them operational on its own. The system was tested quickly.

In 1965, India fought Pakistan again. Ammunition stocks held. Aircraft turnaround times shortened. The machine worked. In 1971, the test was far larger. A full-scale war demanded rapid mobilisation, sustained logistics, and relentless tempo. Indian factories quietly did what speeches and strategies could not. They produced, repaired, and resupplied at scale.

The victory that created Bangladesh was won as much in the industry as on the battlefield. For the first time, India proved that it could fight a modern war without being hostage to foreign factories.

But the very certainty that delivered that success planted the seeds of the next problem.

To guarantee supply, everything was centralised. Budgets flowed in one direction. The government owned the factories, the labs, and the buyers. There was a lack of competition. Private companies took no risk. The pressure to move faster than the plan allowed was purely bureaucratic. The system was designed to ensure availability, not adaptability.

A fortress had been built, and fortresses, over time, have a way of turning inward.

Fortress Becomes a Cage

After 1971, India had finally built what it had always lacked: a defence-industrial backbone.

Ammunition could be produced at home. Aircraft could be maintained and overhauled locally. Warships could be built in Indian yards. Indian scientists were designing missiles. The strength built in that era was slowly becoming rigidity for the next.

Through the 1970s and 1980s, India doubled down on a single model. Defence manufacturing would be owned, funded, and controlled by the state. The Ministry of Defence was the buyer. Public Sector Undertakings were the sellers. DRDO was the designer. There was no market, only allocation.

By the mid-1980s, this machine was enormous. DRDO ran dozens of laboratories working on missiles, radars, propulsion, materials, and electronics. Hindustan Aeronautics Limited had become one of Asia’s largest aerospace firms by headcount, responsible for everything from fighter jets to helicopters. Bharat Electronics supplied radars and communication systems across the armed forces. The Ordnance Factory Board produced vast quantities of small arms and ammunition. Indian shipyards built destroyers, frigates, and submarines.

On paper, India was becoming a major military power. But inside the walls, something else was happening.

The system was optimised for predictability, not pressure. Customers were captive, budgets were guaranteed, and delays barely carried consequences. Projects stretched across decades. There was no competing supplier waiting to take a contract. No export market demands global standards. Innovation moved at the whims of committees.

What India built was reliable, but slow. Sufficient, but rarely cutting-edge.

At the most critical layers, dependence remained. Engines, avionics, seekers, sensors, and high-end electronics still came from abroad. As long as foreign pipelines were stable, the system appeared strong. The fortress held because the outside world cooperated.

Then the outside world began to change.

In the late 1980s, the Soviet Union, India’s primary defence partner, started to unravel. Supply chains weakened, impacting spares that became harder to source and technology transfers that slowed. The very model designed to protect India from uncertainty was suddenly exposed to it.

The lack of competition problem was now rearing its head

India had built production capacity for fighting, but not an ecosystem. There were no private firms pushing DRDO to move faster. Defence innovation was trapped inside a closed loop that rewarded continuity over speed.

What had once been a fortress against vulnerability was now a closed operating system. It has all the traits of one. It was stable, secure, and increasingly incompatible with the pace of technological change outside its walls. The system design choices had left India incapable of being nimble.

By 1991, India still had ships, missiles, and aircraft. But it also had ageing platforms, long development cycles, and rising dependence on imports for the most advanced components. The system that had delivered resilience in one era was beginning to constrain it in the next.

The fortress had done its job, but it had become a cage. It needed to be flung open.

Open Economy, Closed Defence

In 1991, India opened its doors to the world.

Capital flowed in. Private enterprise took off. Software, pharma, and manufacturing were suddenly competing globally. A new Indian economy was being born. But one sector remained almost entirely sealed off from this transformation.

Defence.

While IT, pharma and manufacturing were liberalised, defence procurement and production remained locked inside the same fortress built after 1971. The Ministry of Defence was still the only buyer. PSUs were still the only real suppliers. DRDO still controlled design. Private capital was not allowed anywhere near the battlefield.

This would have been okay if warfare had stayed industrial.

It did not. The Cold War was ending. The Soviet Union, India’s biggest defence partner, was collapsing. Supply lines that had once been guaranteed suddenly became uncertain. India had built a system that was safe only as long as Moscow was stable, which it no longer was.

At the same time, warfare itself was being reinvented.

The 1991 Gulf War showed what modern war looked like. Precision-guided bombs, GPS-guided navigation, satellite imagery, real-time battlefield data, and electronic warfare. The United States destroyed the Iraqi military not by overwhelming numbers, but by overwhelming information.

India watched that war from afar. It did not yet realise how badly this would matter.

Because on paper, India was a major military power. But beneath that power sat a dangerous truth. India was still one of the world’s most import-dependent defence forces.

By the mid-1990s, nearly 70% of India’s major defence equipment, aircraft, artillery, tanks, sensors, and avionics were imported. India controlled around 11% of global arms imports, making it the world’s largest buyer of foreign weapons. Due to the lack of investments allowed in the category, there was nothing it could do.

India had factories, but it still did not control the most critical technologies. India watched it unfold on television screens. And then, in 1999, it showed true weakness. Kargil was not a large war, but it was revealing. Pakistani forces and infiltrators occupied high-altitude positions on the Indian side of the Line of Control. Indian troops had to climb steep, icy slopes under fire to dislodge them.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95dEWr--SX4

India’s real weakness was revealed outside of the slopes, in the command rooms.

India had no indigenous high-resolution tactical surveillance satellites and no domestically produced UAVs that could provide persistent battlefield imagery. It did not even have its own navigation system and depended on foreign GPS. For maps, imagery and some targeting data, India had to rely on external partners.

Indian forces effectively had guns, but they did not have eyes. The nation completely lacked what helped the US win the Gulf War.

Kargil forced emergency imports of laser-guided bombs, surveillance inputs, and targeting assistance. The war was won by sheer courage and tact, but it revealed something terrifying. India’s defence industry was built for the wars of the 1970s. The wars of the 2000s would be run by satellites, sensors, and software.

The fortress had protected India from supply shocks. It had not prepared India for information warfare. That contradiction would drive the next phase.

No Line of Sight

Kargil was not a lesson about courage. India never lacked that.

It was a lesson about something colder and more structural. Modern war was now being decided before the first firefight, in the layer above the battlefield where surveillance, navigation, communications, and coordination determine who sees first and who moves first.

In 1999, India fought the way it always had, with grit, endurance, and sacrifice. But it fought with delayed vision and borrowed systems. Persistent aerial surveillance was missing. Indigenous UAVs did not exist. Navigation depended on foreign controlled GPS. High-resolution intelligence was limited, delayed, or external. The frontline held, but the command layer operated with constraints. The war was won, yet the unease lingered, because everyone inside the system knew this was not a gap that could be patched indefinitely. In a larger conflict, fighting without control over information would not just be inefficient; it would be disastrous. It would be fatal.

By the early 2000s, India decided to stop borrowing sight.

It soon began to quietly build a space-based intelligence and sensing architecture that rewired how it understood conflict. ISRO expanded a constellation of earth observation satellites capable of monitoring borders, tracking infrastructure development, observing missile activity, and watching naval movements across surrounding seas.

Framed publicly as civilian or dual use, their strategic meaning was unmistakable. For the first time, India could observe its frontiers without relying on borrowed imagery or delayed inputs. Independent eyes in orbit compressed the distance between threat and response.

Visibility reshaped command. Dedicated military communication satellites followed, enabling secure connectivity across land, sea, and air without dependence on civilian networks or foreign infrastructure. Fragmented command centres began to operate as networks. Information moved faster. Decisions that once took hours narrowed into minutes. In modern warfare, shortening that decision cycle is not efficient. It is leverage.

Information had become the opening move rather than an afterthought.

Navigation came next. Kargil had already made one dependence unacceptable: relying on a foreign positioning system in the middle of a conflict. India responded by building its own regional navigation constellation. Aircraft, missiles, ships, and ground forces would no longer lose orientation if external signals were denied. Precision became something India could own, protect, and improve on its own terms.

Control over space became control over time.

All Eyes, Borrowed Hands

By the early 2010s, India had achieved something only a handful of nations could claim. It had built an end-to-end ISR stack from space. Not just satellites in orbit, but a working system that delivered intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance as a strategic layer.

Borders could be observed independently. Movement could be detected earlier. Situational awareness no longer depended on permission. On paper, this marked a major step toward autonomy.

Yet the discomfort did not disappear. It moved lower into the stack.

Even as India mastered satellites and missiles, it continued to import many of the technologies that decide modern war at the edge. High-end sensors, seekers, avionics, electronic warfare systems, engines, and critical electronics still came from abroad. India could see the battlefield more clearly than ever before, but it did not fully control the tools that turn vision into dominance. It had eyes, but the hands and nervous system required for execution remained partly foreign-supplied.

India had built capabilities, but not a competitive industrial engine. Space assets lived inside ISRO. Sensors inside DRDO. Electronics inside public sector firms. The armed forces remained the only meaningful customer. Private companies stayed largely outside the loop. Innovation existed, but it moved slowly, constrained by institutions built for certainty, documentation, and continuity rather than speed, iteration, and hard feedback.

By 2008, the contrast with China sharpened this gap. China fused civilian and military technology through state direction. Commercial electronics, telecom, software, and drone companies were pulled directly into defence through mandates, subsidies, and coercive integration. This closed gaps quickly and at scale.

India’s path was different. Civilian innovation evolved outside the military and entered selectively rather than by force. The trade-off was slower early progress, but greater credibility with partners who value neutrality and fewer geopolitical strings.

Indian engineers were building world-class geospatial platforms, semiconductor systems, and software infrastructure for global markets, just not for the Indian military. Defence remained a closed buyer with closed suppliers at the very moment war was becoming fast, modular, and software-led.

By 2012, India had adapted its vision to see better. It had not yet adapted its engine.

Innovation Gets Ignition

By 2014, India had missiles, satellites, radars and nuclear submarines, but it still did not have a modern defence industry. This model had once kept India safe, but it was now holding the country back.

India was spending more than $50–60 billion a year on defence, yet it remained one of the world’s largest importers of military hardware. In the mid-2010s, over 60% of India’s major defence platforms still used imported engines, sensors, avionics, drones, and electronics, even though India had one of the largest engineering workforces in the world. In a battlefield increasingly shaped by software, AI and electronics, this dependence was becoming a strategic risk.

The Indian state finally acknowledged a simple truth: modern defence could not be built solely by public-sector factories and government laboratories. The technologies that mattered most were being developed by private companies and startups, not by monopolies. So the gates had to open.

Defence manufacturing was brought under the Make in India initiative, and new procurement categories were created that allowed private firms and startups to sell directly to the armed forces. Hundreds of components were placed under import bans to ensure Indian suppliers had a guaranteed domestic market.

But the most radical change came with the launch of iDEX.

For the first time in Indian history, a two-person deep-tech startup could pitch a product to the military, receive funding to build a prototype, and see it tested by real units. Defence stopped being a closed loop between PSUs and generals. It became a platform.

More than 16,000 MSMEs entered India’s defence supply chain within a few years. Defence production climbed steadily, and exports, which had been just ₹686 crore in 2013–14, rose to roughly ₹ 1,000 crore by the early 2020s. India also moved from roughly 70% import dependence in the 1990s to producing around 65% of its defence hardware domestically by the early 2020s.

The rules had changed. Defence was no longer only about what India could buy or build slowly. It was about how quickly it could adapt when the nature of war changed again.

A wave of defence-first startups appeared from here

Democratic Battlefield

By the early 2020s, India was no longer just reforming defence on paper.

It was watching a new kind of war unfold in real time. Ukraine changed everything.

For the first time, the world saw a major conflict where cheap drones, satellite imagery, commercial internet, AI-driven targeting and software-defined warfare mattered more than tanks and battalions. A $2,000 drone could destroy a $10 million vehicle. Civilian satellite imagery could expose troop movements. Encrypted messaging apps could coordinate strikes.

War had become a technological stack. India was paying close attention.

This kind of warfare played directly to India’s strengths. It required electronics, software, sensors, space data, manufacturing at scale and frugal engineering. It did not require trillion-dollar aircraft carriers.

This is where India’s startup ecosystem finally met its defence needs.

Over the past few years, a new layer of Indian defence companies has emerged, mapping almost perfectly to how modern war is actually fought.

At the front line are drones and autonomous systems.

Companies like ideaForge have become India’s largest military drone supplier, with surveillance UAVs deployed by the Indian Army, paramilitary forces and police units. Garuda Aerospace builds and manufactures drone platforms and swarm technologies at scale. Asteria Aerospace supplies tactical drones for ISR. NewSpace Research is building loitering munitions and swarm warfare systems, the same category of weapons that Ukraine has used to devastate Russian armour. This is the layer that replaces soldiers with machines.

Behind that sits the “seeing” layer, electro-optics, thermal imaging and night vision.

Tonbo Imaging builds thermal cameras, weapon sights and surveillance optics used by Indian forces and exported to foreign militaries. Paras Defence manufactures electro-optic systems, drone countermeasures and missile optics. MKU supplies ballistic helmets, body armour and protection gear to over 100 countries. These companies control who can see, who can shoot, and who survives in low-visibility warzones.

Above them sits the space and geospatial intelligence layer.

Pixxel is launching hyperspectral imaging satellites that can detect camouflaged vehicles, fuel dumps and material signatures that normal cameras cannot see. SatSure turns satellite data into intelligence for terrain, borders and logistics. Dhruva Space builds satellite platforms and deploys payloads. Skyroot and Agnikul are building small-satellite launch vehicles that can put defence payloads into orbit on demand. This is India’s version of Planet Labs, Starlink, and military ISR, built on ISRO’s cost advantage.

Then comes the counter-drone, radar and electronic warfare layer.

Big Bang Boom Solutions builds counter-UAV and air defence systems. Alpha Design and Tata Advanced Systems work on radars, avionics and electronic warfare. L&T Defence integrates complex systems into ships, vehicles and air platforms.

This is what keeps the sky from filling with enemy drones.

These companies iterate in months, not years. They integrate commercial components with military-grade systems. They ride India’s electronics supply chains, software talent and manufacturing base.

This is the defence equivalent of what happened in fintech, SaaS and e-commerce a decade earlier.

But here is the most important shift. India is no longer building defence for India alone.

Many of these startups are designed to sell globally. Friendly countries in Southeast Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Eastern Europe are all facing the same challenge: they need modern, affordable defence tech without buying from the US or China.

Glad to see India sit in the middle. It has geopolitical trust, frugal engineering, and now has the policy rails to let startups scale.

This is why India’s defence exports are growing at a record pace. It is no longer just bullets and boots. It is drones, optics, sensors, software and space data.

The fortress has reorganised itself into a marketplace.

And that shift is what makes India increasingly dangerous in the 21st century because it is learning faster than systems built for the last war.

Dark Horse

India’s defence exports by 2024 had surged to ₹23,622 crore within a decade, a 34× increase since 2014

For decades, India’s defence story has been easy for the world to file away. Big armed forces, large budgets, heavy imports, slow procurement, long timelines. A serious market, but not a serious builder.

That filing is now outdated.

“Dark horse” does not mean India suddenly becomes the United States or outbuilds China across every platform. It means India winning in a category the world still underestimates: fast-iteration, software-led defence stacks that compound through feedback loops, not just defence budgets. The area where India lacked for decades had slowly become its strength

That is the mispricing.

The world still treats India like a hardware buyer. What it is not noticing is that India is becoming a builder of systems, and systems compound in different ways. They improve with every deployment. They get cheaper, faster, and harder to counter, not because a country outspends, but because it out-learns.

Perception says India is a slow, import-dependent defence force. The reality is that India has built credible capabilities in drones, optics, counter-UAV, geospatial intelligence, secure communications, and integration layers that align exactly with how modern war is being fought. The implication is not abstract: the next defence winners will not only be countries with the largest budgets, but they will also be countries with the tightest iteration loops, and India is finally building those loops at scale.

This is where India becomes “dangerous”, not in the dramatic sense, but in a precise strategic sense. Dangerous to systems optimised for scale, not speed.

It is easy to get stuck on the final 30–35% of sovereignty India still struggles with, engines, advanced seekers, chips, and high-end electronic warfare. Those are brutally hard, and they will remain hard.

But drone- and sensor-led warfare has changed the primary asymmetry drivers. A country can become disproportionately effective without mastering every heavy subsystem end-to-end if it dominates fast-iterating layers such as autonomy, computer vision, swarming, counter-drone, optics, geospatial intelligence, and rapid integration.

Where exactly is India winning? In drones, optics, counter-UAV, geospatial intelligence, secure comms, and integration layers, where iteration speed matters more than perfect sovereignty. Why now, and not ten years ago? Because the gates opened post-2014, and Ukraine proved in real time that rapid iteration beats heavyweight procurement cycles.

India’s export story also becomes structurally credible here. Many countries want modern defence tech, but they don’t want US procurement politics or Chinese dependency baked into their stack. India sits in a rare middle position: trusted enough to buy from, affordable enough to adopt, and neutral enough to integrate without fear of sudden strings being pulled. That neutrality is not a slogan. It is a product feature.

The defence leaders of the next decade will not just build weapons. They will ship updates.

The strongest defence industries won’t look like steel plants. They will look like living software systems: sensors feeding data into models, models pushing decisions into systems, systems improving with every mission, and feedback loops tightening faster than the enemy can adapt.

The battlefield is becoming an API. India is more than ready to become one for the world.